After a decade of research, the EPA has confirmed that neonicotinoid pesticides are highly toxic to bees and partially responsible for pollinators dying off in record numbers. In light of this, the EPA also concluded that the benefits for farmers of coating soy and corn seed, a common use of 'neonics,' are questionable. However, the EPA has refused to take action to ban or rein in the use of the poisons, opting instead for more time to study them in a so-called 'final assessment.'

After a decade of research, the EPA has confirmed that neonicotinoid pesticides are highly toxic to bees and partially responsible for pollinators dying off in record numbers. In light of this, the EPA also concluded that the benefits for farmers of coating soy and corn seed, a common use of 'neonics,' are questionable. However, the EPA has refused to take action to ban or rein in the use of the poisons, opting instead for more time to study them in a so-called 'final assessment.'

Petition demanding the EPA restrict these toxic pesticides:

https://act.ewg.org/a/bees-neonics-epa-1

The use of neonicotinoid pesticides has increased in the last 10 to 15 years as is evident through reporting by the U.S. Geological Survey and increased detection frequencies in water and food. In the most recently published results of the USDA Pesticide Data Program (testing occurred in 2018, report published in 2019), imidacloprid, a neonicotinoid, was detected in over 83% of raisins, a popular children’s food. Since 1999, imidacloprid has been one of the most widely used neonicotinoid insecticides in the world. Acetamiprid, also a neonicotinoid, was detected on nearly 50% of frozen strawberries. While much of the recent work has focused on the impact of neonicotinoids on bees, a growing body of evidence demonstrates that persistent, low levels of neonicotinoids can have negative impacts on a wide range of organisms.

Since 1993, the Environmental Working Group (EWG) has shined a spotlight on outdated legislation, harmful agricultural practices and industry loopholes that pose a risk to human health and the health of the environment. The watchdog group is most well-known for its annual listing of the "Dirty Dozen," twelve commercial fruits and vegetables that testing has shown are the most contaminated with pesticide residues. One of the organization's current projects is circulating a petition to the EPA demanding that it restrict the use of these pollinator-killing neonicotinoid pesticides now.

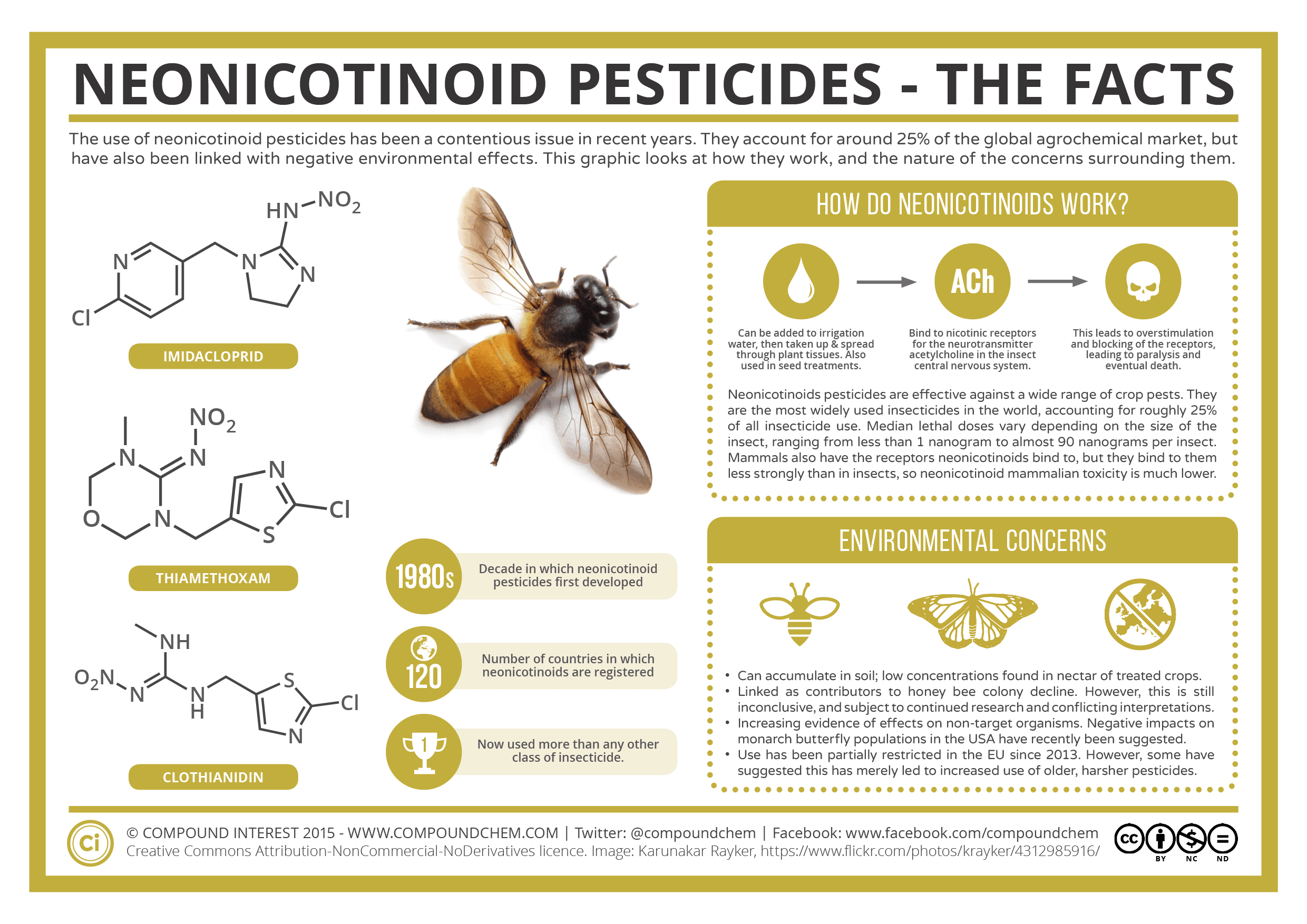

Neonicotinoids are in a class of insecticides known as 'systemic' pesticides because they are intended to be absorbed into the plant tissue of crops they are sprayed on. In other words, they are present in the plant when an insect eats the plant and they are present in the plant when a human eats it. A recent national biomonitoring program administered by the US Centers for Disease Control involving over 3000 American adults, adolecents and children found that children experience higher exposure to neonicotinoids than adults and nearly half of all individuals sampled had detectable levels of at least one neonicotinoid. Research indicates an increased risk of adverse developmental and neurological effects from chronic exposure to neonics.

Only approximately 5% of the neonicotinoid active ingredient is taken up by crop plants and most instead disperses into the wider environment. Neonics dissolve in and are transported by water. They are blown around in dust. Studies show that it takes most neonics more than six months for just half of them to 'dissapate,' remaining toxic to organisms at very low concentrations. Some researchers are concerned that neonicotinoids applied agriculturally might accumulate in aquifers.

Numerous conservation organizations along with EWG and its supporters have campaigned vigorously for years urging the EPA to reconsider its decision to continue allowing the use of noenicitinoids instead of following the lead of European and Canadian agencies to restrict the use of these harmful insecticides.

We cannot stand by and watch pollinators die as the EPA completes its 'final assessment.' At the very least, the EPA should follow Minnesota's lead and require farmers to end all nonessential neonicotinoid use. Farmers who use these chemicals must be required to prove they need them.

Last year, the EPA proposed interim decisions for neonics acetamiprid, clothianidin, dinotefuran, imidacloprid, and thiamethoxam. The EPA says the proposals "contain new measures to reduce potential ecological risks, particularly to pollinators, and protect public health." However, what EPA is proposing (even if they are just 'interim decisions') appears to fall far short of what is needed given the critical depletion of pollinator populations.'

EPA is proposing the following (in italics) but has not issued a final rule yet. Remarks about the proposals are in brackets '[ ]'

Management measures to help keep pesticides on the intended target and reduce the amount used on crops associated with potential ecological risks;

[Will these 'management measures' be mandatory? If only 5% of the active ingredient is absorbed, that means no matter how much less you use or how much better you make it stick to its target, there's still going to be 95% of it remaining in the environment.]

Requiring the use of additional personal protective equipment to address potential occupational risks;

[Yes, but this just reinforces the fact that neonics are a poison to humans. Keeping farmworkers safe from large-dose exposures on the job is important, but studies of human health effects also indicate toxicity at very low levels. One area that needs more study is how residues of mixed types of neonics interact with each other and whether any synergistic effects of the toxic mixtures pose even a greater health risk.]

Restrictions on when pesticides can be applied to blooming crops in order to limit exposure to bees;

[Some proposed policies suggest that maybe neonics should be reserved for non-flowering crops that won't produce pollen that threatens pollinators. Neonic-treatment of any crop type represents an additional pathway of neonicotinoid exposure to other organisms simply by their presence.]

Language on the label that advises homeowners not to use neonicotinoid products;

[The EPA should not be in the business of keeping up the profits of the corporations that it regulates. This proposed rule is just that. If the EPA believes that neonics pose a risk, it should prohibit the residential use of them, not 'advise' that folks don't use them. Homeowners don't have a right to use any chemical they want and corporations don't have a right to profit from selling poison. If banning the sales of neonics to homeowners hurts a chemical company's profits, well, that's the cost of doing business when you sell poison.]

Cancelling spray uses of imidacloprid on residential turf under the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA) due to health concerns;

[The scientific knowledge base on the toxicity of the various neonicotinoids is still being developed. The effort to develop a more comprehensive health hazard assessment of neonics is impeded because data from proprietary studies (usually performed by the corporations being regulated) that are available to EPA, which likely contain relevant toxicological data that would complement publicly-available data, are not available to independent researchers. Imidacloprid, subject of this proposed EPA ban, is one of the most studied neonics. A 2020 review of all scientific research to date on the potential human health effects associated with exposures to neonicotinoid pesticides revealed 127 studies of imidacloprid compared with acetamiprid (34), clothianidin (23), dinotefuran (4), nitenpyram (7), thiacloprid(20) and thiamethoxam (23). It would appear that the more study a neonic receives, the more likely enough problems will be found with it to warrant the EPA banning it. Why wait? In general we know the pollinator issue itself warrants banning neonics. EPA needs to ban them all now. We've entered an era when we need zero tolerance for having our bodies and ecosystems assaulted by synthetic chemicals whose only purpose for existing is to be sources of profit for corporations. No more profit from ecocide!]

Petition demanding the EPA restrict these toxic pesticides:

https://act.ewg.org/a/bees-neonics-epa-1